There are only two planets that orbit closer to the Sun than the Earth. As such, Mercury and Venus are known as “inferior planets,” but as any astronomer will tell you, there’s nothing inferior about these worlds. Both present their own unique challenges while providing ample rewards for the patient observer. But what can you hope to see from Earth’s closest siblings?

Mercury, the Elusive Planet

Both Mercury and Venus are visible to the naked eye and have been known for thousands of years. Of all the planets, Mercury orbits closest to the Sun and is therefore the fastest moving against the background sky. Early observers soon noticed this and named the planet accordingly.

The Babylonians called it Nabu, the Greeks named it Hermes, while the Romans gave it the name we know today - Mercury. All these names originally belonged to fleet-footed messengers in mythology - a fitting name for a planet that appeared to dart back and forth between the early morning and evening twilight skies.

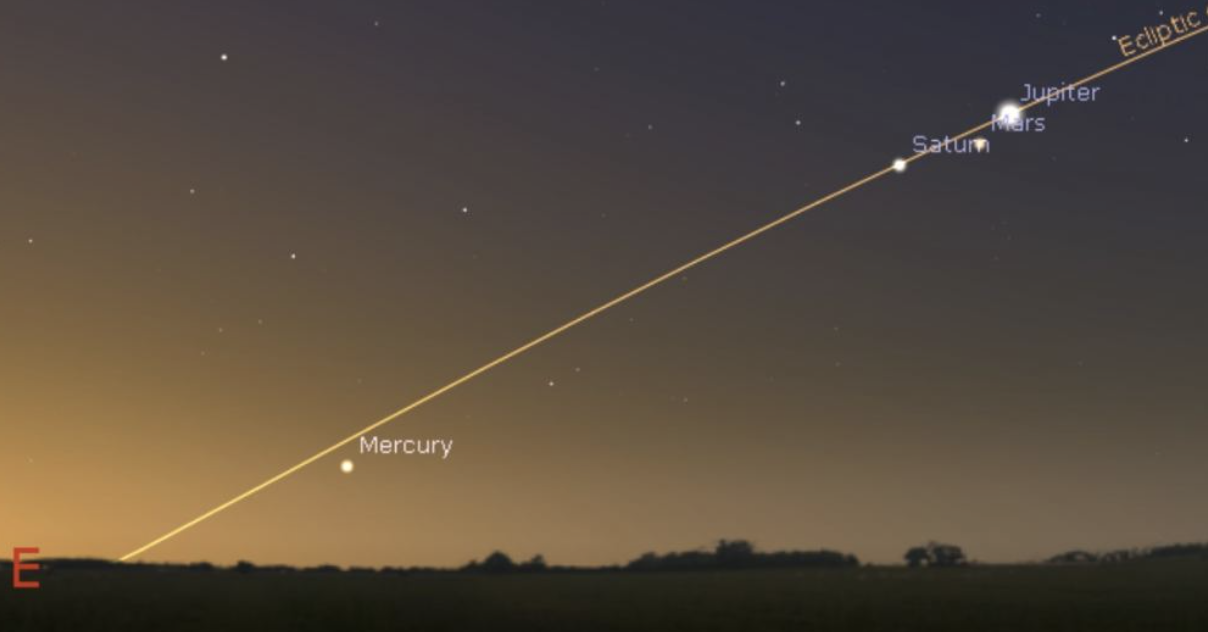

Unfortunately, this makes Mercury a challenge for naked eye observers. With an orbital period of just 88 days, it’s typically only visible for a few weeks at a time before it’s swallowed by the Sun’s glare. There’s an added complication; since the planet is closest to the Sun, it never strays more than 28 degrees from the Sun in the sky.

As a result, even at its best, it’s typically only visible for about 30 minutes in the predawn or evening twilight and is often seen very low down in the sky. You’ll need a clear, unobstructed view, with few trees or buildings blocking your view, as the planet is unlikely to appear higher than about ten or twelve degrees above the horizon.

(This has to do with the ecliptic, the path of the Sun, Moon and planets across the sky. At these times, when the days and nights are of equal length, the ecliptic is at a favorable angle to the horizon, allowing the planet to appear higher in our sky.)

Experienced observers also know that the Moon can be an easy and convenient marker for Mercury. A thin, crescent Moon, just a day or two from new, can sometimes be seen close to the planet. Scanning the area surrounding the Moon with binoculars can help to reveal the planet before it becomes apparent to the naked eye.

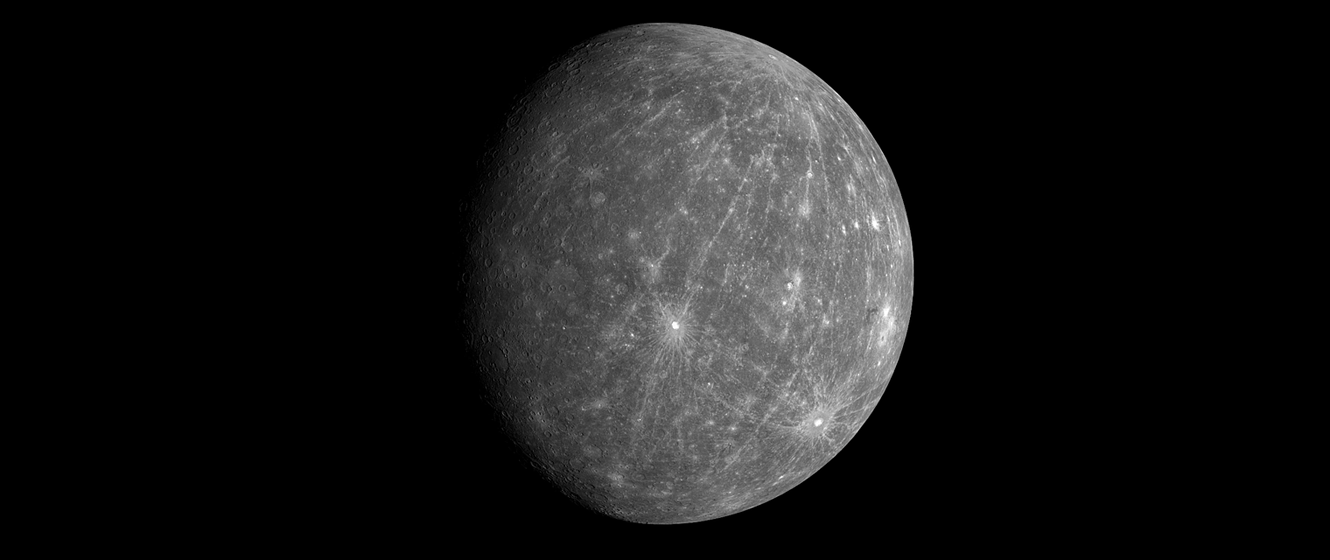

What does Mercury look like? Most planets distinguish themselves from stars by their brightness and the fact that they don’t twinkle, but Mercury is an exception. It can be bright, but because it appears against a twilight sky, it often appears fainter than it otherwise would. Similarly, due to its low altitude, its light has to travel through thicker layers of air, causing it to twinkle.

It does have one attribute in its favor: it has a fairly unique color. It frequently can be seen shining with a pinkish-white light, which helps to make it stand out against the twilight. If the Moon isn’t around to help you spot it, another planet might also be nearby, with Venus being a frequent companion to Mercury.

Venus, the Shining Beacon

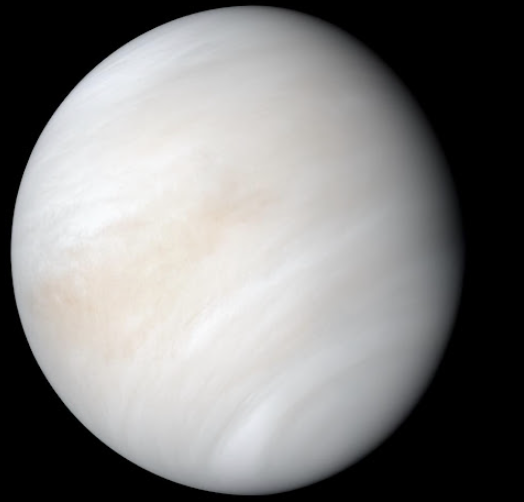

Unlike Mercury, Venus is visible for months at a time and appears as a brilliant white “star.” In fact, after the Sun and Moon, Venus is the third brightest natural object in the sky and can appear quite beautiful when the Moon or another planet is nearby.

No wonder then that the ancients named it after their goddess of love. To the Babylonians, the planet was known as Ishtar, the Greeks knew it as Aphrodite and, of course, the Romans gave it the name we know it by today.

Venus can stray away from the Sun by as much as 48 degrees, which means it can be visible for several hours either before sunrise or after sunset. It’s almost unmistakable in the sky - assuming you know what it is.

When the planet is low, its light has to pass through thicker layers of atmosphere, causing it to prominently flicker a multitude of colors. As a result, it’s often been reported as a UFO by unsuspecting members of the public!

Planets with Phases

Unfortunately, neither Mercury nor Venus yield much to the binocular observer. Mercury’s disc is simply too small to be apparent, but you might have a little more luck with Venus.

Since both planets orbit closer to the Sun than the Earth, they both show phases like the Moon. For example, when either planet is on the opposite side of the Sun from the Earth, you’ll see a fully illuminated disc, like the full Moon. (Assuming the planet isn’t too close to the Sun in the sky.)

When Mercury and Venus are at their greatest distance from the Sun in the sky, their discs will be half-illuminated, like the half Moon we see at first and last quarter. When the planets are between the Earth and the Sun, the darkened hemisphere is turned toward us and the planet becomes almost impossible to see - like the new Moon.

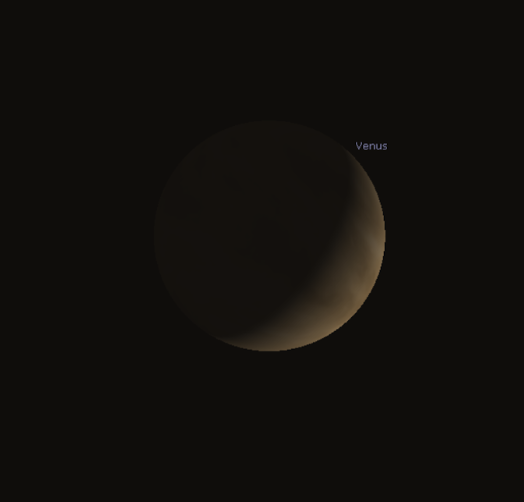

Decent binoculars (typically 10x50 or better) will show the half moon and crescent phases of Venus. The crescent phase is visible between the half moon phase (when Venus is at its best) and the new moon phase (when the planet is between the Earth and the Sun) in the evening sky.

Conversely, the crescent phase is also visible after Venus has moved away from the Sun and is headed toward its best visibility in the morning sky.

The View Through a Telescope

Will a telescope provide better views? To some extent, yes. A low power of 35x is just about enough to show the disc of Mercury, but you’ll need to increase the magnification to about 100x to easily see its phases. The planet shows a brownish-tan hue through the eyepiece. If you have a larger telescope with an aperture of about 250mm or more, you may be able to see some surface markings on the tiny world. Using an orange filter might help to bring out these features.

While Mercury can be observed either shortly before sunrise or shortly after sunset, you’re advised to try observing Venus during daylight hours. The planet’s light is so brilliant that the contrast between its disc and the dark background sky is often too great. By observing during daylight hours, the planet is fainter and, therefore, the contrast between its disc and the sky is a lot less.

It used to be quite tricky to accomplish this - after all, despite its brightness, Venus is not apparent to everyone in broad daylight - but smartphone apps and guided telescopes have made the task a lot easier. Besides the lower contrast, there’s one other benefit to observing during daylight. The planet is much higher in the sky, where the air is more stable. As a result, you’ll see a clearer view through your eyepiece.

Like Mercury, a low power is all that’s needed to show its phases. Also like Mercury, with a larger scope you may be able to discern some markings, but you won’t be looking at the surface of the planet. Venus is entirely enshrouded in clouds, making its surface impossible to see through a regular telescope from Earth. However, you might still be able to see some faint cloud patterns in its atmosphere.

Rare Events for the Lucky Observer

You might also be able to spot an unusual phenomenon, the cause of which is still unknown. The Ashen Light is similar to Earthshine on the Moon, and happens when Venus appears as a thin crescent and the whole of the planet’s disc becomes visible.

Scientifically, the phenomenon has yet to be confirmed, but there have been enough observations over the years to warrant further study. If real, it’s thought the darkened hemisphere may be illuminated by lightning in the planet’s atmosphere.

There’s one other phenomenon you can (theoretically!) observe with both planets: a transit of the Sun. This happens when the planet passes between the Earth and the Sun and the planet appears to slowly move across the Sun’s face.

This is a rare event, especially for Venus. In fact, if you haven’t already seen Venus transit the Sun, you never will. Unfortunately, it only happens for Venus twice every one hundred years, with roughly eight years between each occurrence, and both transits have already taken place this century. The first was in June 2004 and the second was in June 2012.

Transits of Mercury are a little more frequent, but you’ll still have to wait at least three years between each one. The gaps are always three, seven, ten, or thirteen years between each transit; for example, following the transit of November 11th, 2019, there’s a thirteen-year wait before the next in 2032. There’s a seven-year gap before the next, in 2039, then a ten-year wait until 2049, and then, finally, a three-year gap until 2052.

Each transit can last up to about seven hours. During this time, you’ll see the silhouetted disc of Mercury appear as a tiny black dot against the bright background of the Sun. You should never look directly at the Sun through a telescope without first taking precautions.

Alternatively, you can project an image of the Sun onto a piece of card, but be sure to use a very low magnification eyepiece.

Mercury and Venus may not have the stunning rings of Saturn or the Earth-sized storms of Jupiter. Similarly, neither planet has moons that dance about their discs, but both worlds still provide challenges and can develop your observing skills. Can you see Mercury in the twilight? Is the ghostly Ashen Light fact or fiction? What markings appear through the eyepiece?

Catch Mercury before it disappears, swallowed by the Sun’s light. Savor Venus as it shines beside the crescent Moon or the other planets. Once you appreciate these planets, you’ll never think of either world as inferior, but rather as companions whose gifts are rarely easily surrendered but still richly rewarded.

Learn More

Interested in learning more about telescopes and astronomy? Not sure where to begin? Check out our Astronomy Hub to learn more!