Banner Image Credit: Lu Shupei

Orionid Meteor Shower: A Summary

What Is the Orionid Meteor Shower?

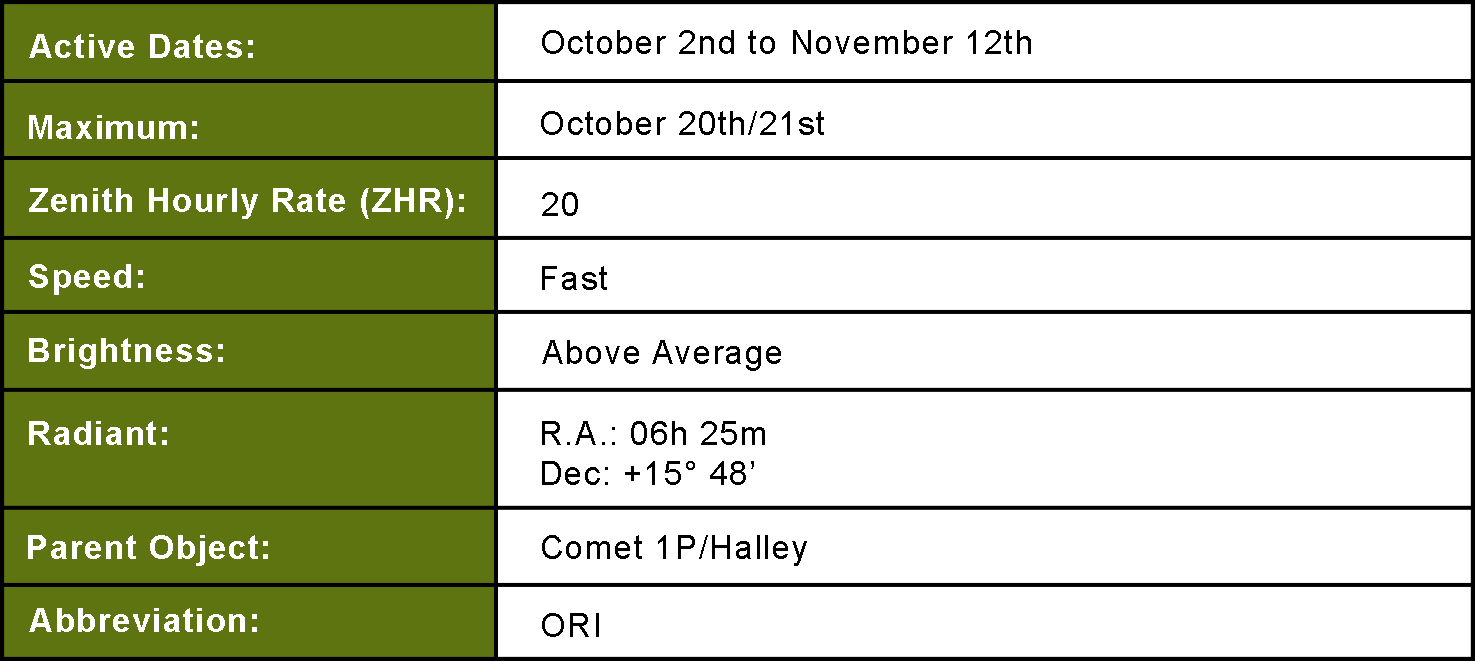

The Orionids are one of two major showers that occur during the fall, with the other being the Leonids of November. At first glance, the Orionids and Leonids may seem to be the meteor equivalent of twins, but look closely and you’ll start to notice a few subtle differences. They’re both about the same brightness, and they both last about 40 days, but while both showers produce fast meteors, the Orionids are a little slower and are therefore potentially a little easier to spot. With a zenith hourly rate (ZHR) of 20, the Orionids are also slightly more active than the Leonids.

Lastly, they both occur in the autumn, with the Orionids being the first to reach maximum, around October 21st, and the Leonids following suit about three weeks later, around November 17th.

All this being said, there’s one deciding factor that ensures the showers cannot be twins: they have different parent bodies. In the case of the Leonids, the parent body is Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle, whereas the Orionids have a far more famous parent: Comet 1P/Halley. (Incidentally, the Orionids are not an only child, as they do have a sibling. The eta Aquariids in spring share the same parent, making Halley the only comet known to be the parent body of two showers.)

A Brief History of the Orionid Meteor Shower

The first observations of the Orionids date back nearly 2,000 years, with outbursts being identified in both Chinese and Japanese records as early as 585 AD. A potentially earlier observation dates back to 282 AD.

However, it wasn’t until 1839 that the shower was first discovered, independently, by the American astronomer Edward Herrick and the Belgian-French astronomer Adolphe Quetelet. The first precise location of the radiant was determined in 1864, and while the Austrian astronomer Rudolf Falb suggested a connection between Comet Halley, the Orionids, and the eta Aquariids in 1868, it wasn’t until the late 20th century that the link between the comet and the Orionids was confirmed.

The Orionids’ nearly-twin shower, the Leonids, are famously prone to outbursts every 33 years or so, but the Orionids have been known to put on a show too. Historically, outbursts have occurred on at least seven occasions, with the most recent being in 2006, when observers recorded a zenith hourly rate of more than 100 at the shower’s peak. (While this can’t compare with the thousands typically produced by the Leonids during a meteor storm, the activity of the Orionids on that occasion was still five times higher than usual.)

Another potential outburst is predicted for 2070, when the Earth encounters particles that may be in an orbital resonance with the planet Jupiter.

How Can I Observe the Orionid Meteor Shower?

The Orionids have their radiant about ten and a half degrees northeast of the star Betelgeuse in Orion, on the border with neighboring Gemini, the Twins. That being the case, you’ll find it about four degrees west of Alhena, the star that marks the foot of Pollux, and roughly midway between that star and Xi and Nu Orionis, the two stars that mark the elbow of Orion’s raised right arm.

As with most meteor showers, the Orionids are best observed in the predawn hours, with the radiant rising at around midnight in the east. It’ll reach an altitude of 30 degrees, and therefore above the thicker air close to the horizon, at around 1:30 AM, and then culminates roughly four hours later. For many, the sky then starts to brighten shortly after.

This being the case, any time between 1:30 AM and 5:30 AM is a good time for the Orionids, with 5:00 AM as a potential optimum time, as the radiant will be close to its highest point and the skies will still be dark.

If you’re outside closer to midnight, look towards the northeast and southeast. If you’re outside closer to dawn, look towards the southeast and southwest.

A 10 Year Forecast

The table below shows the Moon phase and planets that may be visible above the horizon at 5:00 AM on October 21st of each year. It should be noted that (again, as with all meteor showers) the date of the maximum can vary a little from year to year, and the exact timing isn’t typically known until the International Meteor Organization releases its annual report.

With that in mind, although the Orionids are often at their best on the evening of the 20th and in the early hours of the 21st, they can occasionally peak on the evening of the 21st and in the early hours of the 22nd.

In terms of the rating, if the Moon is below the horizon at that time, then its light won’t drown out the fainter meteors, and the rating is five stars. However, if the Moon is above the horizon, then the rating is based upon the phase, altitude, and distance of the Moon from the radiant at that time.

Lastly, if the Moon is in the western hemisphere and more than half full, it might be best to wait for the Moon to set before stepping outside. If the Moon is waning and half full or a little less, then it’s best not to wait to observe the shower, as the Moon will only rise higher as the night progresses, potentially causing more interference as its altitude increases.

Learn More

Interested in diving deeper into the world of astronomy? Check out our AstronomyHub for a wealth of articles, guides, local resources for planetariums and observatories near you, and more to enhance your stargazing experience.