As almost everyone knows, there are currently eight planets in the solar system. Five of them - Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn - are easily visible to the naked eye and were first observed in ancient times. Two others, Uranus and Neptune, were discovered after the invention of the telescope, and the eighth, of course, is the Earth.

Not so long ago, there were nine planets, but Pluto is now considered a dwarf planet. What happened? Why is Pluto no longer a planet? And what is a planet, anyway?

The Five Wandering Stars of Ancient Skies

When ancient astronomers first looked up at the stars, they noticed that five of them appeared to move. Clearly, these were no ordinary stars, and so they called them planetes, the Greek word for “wanderers.”

Before the invention of the telescope in the early 17th century, astronomers knew very little about these strange stars. No one knew there were other worlds beyond the Earth and Moon until Galileo turned his telescope toward Jupiter in 1610.

What he saw would revolutionize our understanding of the universe and our place within it. There was a distant world, with four moons of its own, and with this single discovery, the definition of a planet changed.

The planetes were no longer considered to be wandering stars or gods, and the Earth and Moon were no longer the only worlds in the universe. Suddenly, almost literally overnight, the Earth became just one of six known planets in the solar system - but how many others were there?

The Solar System Expands

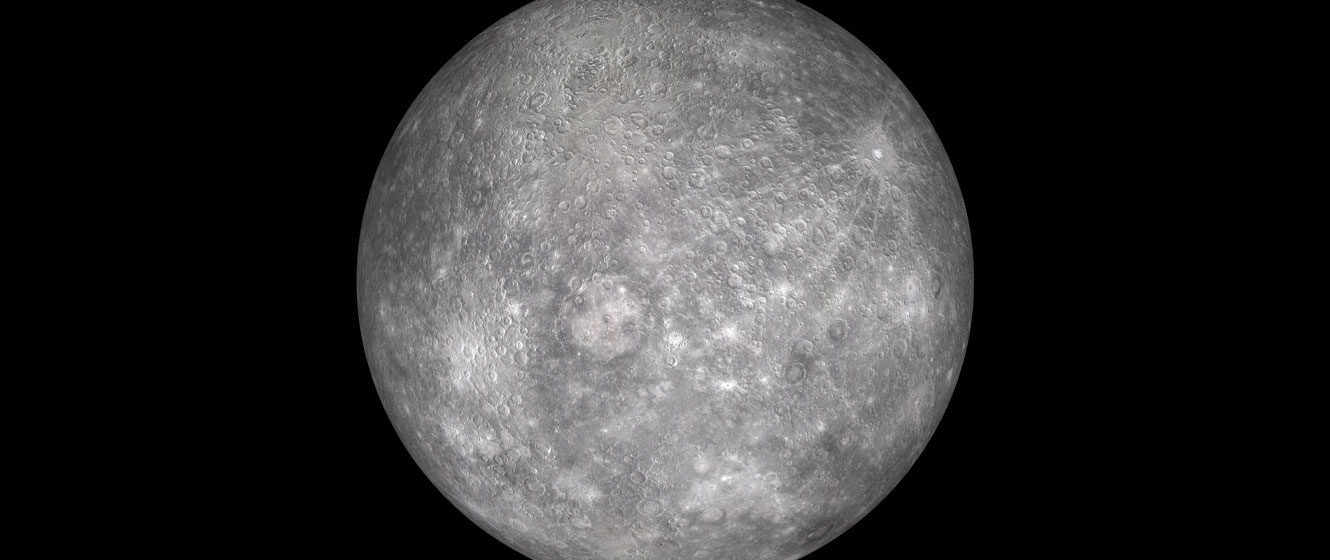

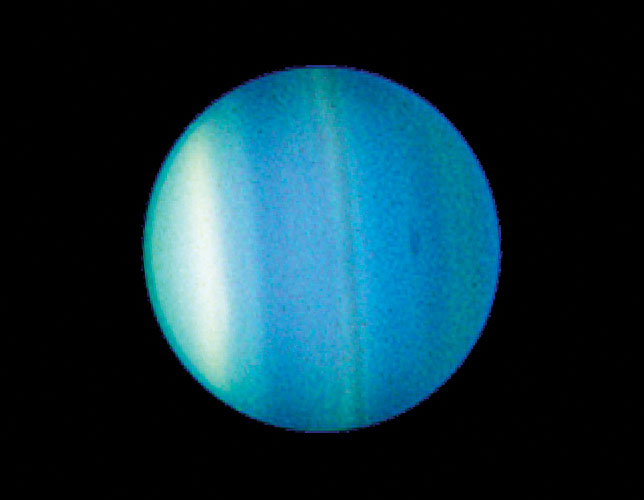

Image Credit: NASA, ESA, A. Simon (Goddard Space Flight Center) and M.H. Wong (University of California, Berkeley)

The discoveries kept coming over the next 180 years. Mercury and Venus showed phases like the Moon, Mars revealed polar ice caps, the Great Red Spot raged in Jupiter’s atmosphere and rings encircled Saturn. Then, one night in March 1781, William Herschel was scanning the stars of Gemini when he came across something unusual.

It appeared to have a tiny, pale blue-green disc, but as new worlds had yet to be discovered beyond the six already known, he initially thought he’d discovered a comet. In fact, Herschel had found the seventh planet from the Sun, later to be named Uranus.

The solar system grew again on New Year’s Day, 1801, when the Italian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi discovered Ceres. Given that it never showed a disc, but only appeared starlike, and having calculated that it orbits between Mars and Jupiter, astronomers surmised it must be tiny in comparison to the other worlds. (It’s now known that Ceres is only 587 miles in diameter, whereas the Earth is 7,917 miles).

All the same, astronomers announced the discovery of a new planet, bringing the total up to eight. But this new world was not what it seemed.

Starlike Worlds, Not Planets

In March 1802, just 14 months after the discovery of Ceres, the German astronomer Wilhelm Olbers found a second world between Mars and Jupiter. Astronomers announced this second world, later named Pallas, as the ninth planet, but not everyone was convinced.

William Herschel, the discoverer of the planet Uranus, reviewed the data relating to the two new worlds and compared it to the properties of comets and the other planets. He concluded the new worlds were not planets at all, but he didn’t believe them to be comets either.

Since these worlds were so small compared to the planets and given that they appeared starlike through telescopes, he suggested a new category instead: asteroids. The term, meaning “starlike,” was certainly appropriate, but the astronomical community didn’t fully adopt the term for another century.

However, as more of these worlds were discovered, astronomers acknowledged they were in a different league from their larger neighbors. Therefore, they also became known as “minor planets” and the number of “major” planets dropped to seven again.

The Eight Ball and the Odd-ball

Besides being the first planet to be discovered telescopically, Uranus had another unique attribute: it wasn’t where it should be. The planet appeared to stray from its predicted position, as though another celestial body was acting upon it. The answer was obvious: there must be another large planet beyond it. This undiscovered world must also be massive enough for its gravity to pull Uranus slightly out of orbit.

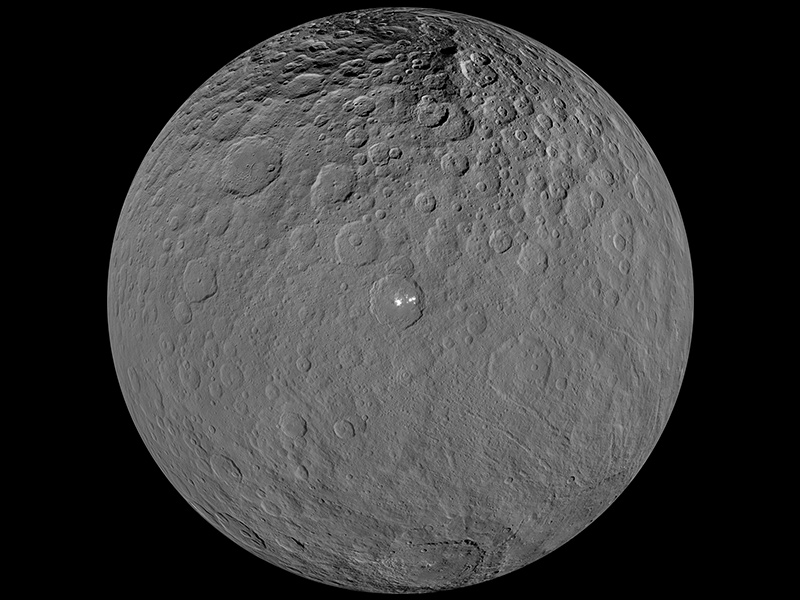

Image Credit: NASA/Space Telescope Science Institute

If Uranus was the first planet to be discovered with a telescope, then Neptune was the first to be discovered with math. Working independently, John Couch Adams in England and Urbain Le Verrier in France both analyzed the orbit of Uranus. Both accurately calculated the predicted position of the unseen planet, but it was Johann Gottfried Galle in Germany who discovered it.

With the planetary tally back up to eight, it appeared as though the solar system was finally complete, but something was still amiss.

Neptune, like Uranus before it, was also showing discrepancies in its orbit. The American astronomer Percival Lowell was the first to notice the problem around the start of the 20th century.

Not unreasonably, he suspected that a ninth, more distant and massive world lay in the far reaches of the solar system. In 1906, he began his search for the world he dubbed ‘Planet X.”

Unfortunately, Lowell died in 1916, and responsibility for the search eventually went to Clyde Tombaugh, a young astronomer at Lowell’s observatory.

On February 18th, 1930, Tombaugh was reviewing images taken the month before when he noticed a faint star that had apparently moved. Tombaugh had found Lowell’s “Planet X.” The discovery of a ninth planet was subsequently announced, and the distant world was named Pluto.

Unfortunately, once again, something wasn’t right. Pluto doesn’t orbit the Sun like the other planets. It has a unique orbit that’s both inclined by 17 degrees and that brings it closer to the Sun than Neptune. Its mass is also far less than required to account for the orbital discrepancies of Uranus and Neptune.

(That mystery was resolved when the space probe Voyager 2 flew past Uranus and Neptune in the 1980s. Data from the probe allowed scientists to more accurately assess the masses of both planets and, therefore, provided a better understanding of their orbits).

Pluto’s Planetary Status is Questioned

Image Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

Despite these oddities, Pluto kept its planetary status, but astronomers started to have their doubts. In 1992, astronomers David Jewitt and Jane Luu announced the discovery of an object at a similar distance from the Sun as Pluto, and further discoveries of additional objects soon followed.

Clearly, Pluto was not alone in the outer reaches of the solar system. While Pluto remained the largest of the bunch, astronomers asked questions. Are all these new worlds planets? Or is Pluto something else?

The tipping point came in 2005 with the discovery of Eris. Initially thought to be larger and more massive than Pluto, the media hyped it as Planet 10, but calmer heads prevailed. Hundreds of objects were now known to be moving through the same cold, distant space as Pluto, and it seemed likely there were more.

The existence of tens, or even hundreds, of planets suddenly seemed possible. No one had ever clearly defined what a planet was. The perception that planets must orbit the Sun was not only vague but also inaccurate. Asteroids, for example, also orbit the Sun. So what, exactly, is a planet?

The International Astronomical Union Defines a Planet. Mostly.

In 2006, the members of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) met in Prague for their General Assembly meeting. Following several days of debate and wrangling, the members voted and agreed to the following definition:

A “planet” is a celestial body that: (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for itself-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, and (c) has cleared the neighborhood around its orbit.

In plain English:

- The world has to orbit the Sun and not another body. Therefore, the moons of planets cannot be planets themselves, regardless of their size or mass.

- The world has to be (nearly) spherical. Since the vast majority of asteroids are potato-shaped, this means they cannot be planets either. However, the term “nearly round” remained undefined.

- The world cannot share its neighborhood with other worlds. The world needs to have cleared out, or swept up, any material that might lie along its orbit.

The last point has proven to be especially controversial, as it’s very ill-defined. For example, must the world be the only object along its orbit or is some material allowed to remain? If so, which material can orbit alongside the planet?

On the face of it, these might not seem like major concerns, but consider this: the Earth regularly encounters clouds of comet debris that form the basis of meteor showers. Jupiter shares its orbit with a class of asteroids called Trojans. If we were to follow the IAU’s definition to the letter, then neither the Earth nor Jupiter are actually planets.

Pluto is Demoted While Ceres is Promoted

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA

Since, according to the IAU, Pluto no longer fit their definition of a planet, it needed to be reclassified. Therefore, the IAU created a category for objects that were planet-like but didn’t quite meet the planetary criteria. The result? Dwarf planets.

A “dwarf planet” is a celestial body that: (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for itself-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, (c) has not cleared the neighborhood around its orbit, and (d) is not a satellite.

To translate, it must be round-ish, in orbit around the Sun (and so, not a moon) and it must share its neighborhood with other objects. Again, the term “neighborhood” was not clearly defined.

Pluto, therefore, lost its status as a planet and became a dwarf planet instead. Ceres and Eris, the “10th planet” discovered the year before, also joined the club. The solar system shrank down to eight planets again.

While being both confusing and controversial (both within and without the astronomical community), it also leaves a potential pothole in the road to planetary status. If a world larger than Mercury were to be discovered in Pluto’s “neighborhood”, it would be classified as a dwarf planet, despite being larger than the smallest of Earth’s siblings.

For the time being, at least, there are officially eight planets in the solar system. However, when it comes to asking the question “what is a planet,” the answer has always had a footnote that reads *subject to change.

Learn More

Interested in learning more about the planets in our solar system and beyond? Not sure where to begin? Check out our Astronomy Hub!

This Article was Last Updated on 08/18/2023