Why Photograph A Comet?

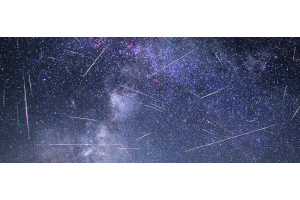

Comets are unique in that they are both rare and visually stunning. Unlike stars or planets, comets can be infrequent and unpredictable with their timing. For example, the last truly “great” comet was Comet McNaught in 2007; and before that, Comet Hale-Bopp in 1997. And even though large observatories operated by NASA or other organizations can photograph comets in great detail, the scale of these celestial ice balls is often too great to be fully appreciated by such dedicated telescopes and can only be truly appreciated by wide-field telescopes and lenses.

Halley's Comet is one of the most famous and well-documented comets, known for its roughly 76-year orbit around the Sun. In 1986, it made its most recent appearance, passing through the inner solar system and offering a rare observational opportunity for astronomers and the public. Although it was less bright than expected, largely due to unfavorable positioning with respect to Earth, spacecraft like Giotto provided close-up images of the comet's nucleus for the first time. Halley's next appearance is expected in 2061, and it will likely offer a much more favorable view, as its proximity to Earth during the pass will be closer, making it brighter and easier to observe with the naked eye. Upcoming comets, such as C/2023 A3, are perfect targets for ultra-wide camera lenses and telescopes, making it possible to capture their full beauty across the night sky. Even modern smartphones, equipped with sensors that have an increasingly high resolution and low-light capability, can yield impressive results when photographing these celestial visitors. At the bare minimum, you’ll need a smartphone with the ability to take a 2-3 second exposure, a tripod, and some sort of adapter. Those wishing to take more stunning photos will need either a dedicated deep-sky astrophotography camera, DSLR, or a telescope/camera lens with a focal length of less than 400mm.

It’s only in the last few decades that the ability to photograph comets has become commercially viable to amateur astronomers. Although images of comets like Hale-Bopp exist, previous comets could only be practically photographed with film cameras, expensive trackers, and with optical glass that suffered from chromatic aberration and other optical issues. Now, taking stunning photos of comets can be done with a wide variety of devices that don’t break the budget. This article will expand upon options you can consider to take a beautiful photo of the next great comet, as advancements in digital technology have made comet photography more accessible than ever before. As we look forward to Halley's return, hobbyists and professionals alike will be able to leverage these technologies to capture this legendary comet in ways unimaginable during its last visit.

A Brief Overview of Historical Comet Observations

Comets have been seen throughout antiquity. In 1066, a comet was spotted in the sky, prompting William of Malmesbury, an English historian, to remark in terror: “You've come, have you?’, he said. ‘You've come, you source of tears to many mothers. It is long since I saw you; but as I see you now you are much more terrible, for I see you brandishing the downfall of my country." Later, a comet was spotted in 1456 and was considered an omen of doom after the Ottoman Empire besieged the city of Belgrade. A comet was also spotted in 1145, 1222, and 1301, each apparition appearing to portend doom or disease. However, it was not until the 16th century that it was noticed by Edmund Halley that these comets were in fact the same one, appearing every 75 years. This was the first time a comet could actually be predicted. Halley’s comet, of course, had its notable (or perhaps not-so-notable, depending on your point of view) display in 1986 that paled in comparison from showings in the past due to poor celestial geometry. Halley's next appearance is expected in 2061, and it will likely offer a much more favorable view, as its proximity to Earth during the pass will be closer, making it brighter and easier to observe with the naked eye.

Other, non-periodic comets have made their presence known throughout history in the sky. Perhaps the most famous example in the last 50 years was Comet Hale-Bopp, discovered in 1995 by the astronomers Alan Hale and Thomas Bopp. The comet had an unusually long observation arc, being observed naked-eye visible for over 18 months in 1996 and 1997. This comet undoubtedly is what you first think of when you think of a comet, as its incredible 40 kilometer nucleus put on a dazzling display. Another group of brillant comets are those belonging to the Kreutz sungrazer class, many of which have gone on to become great comets. There was Comet Ikeya-Seki in 1965 that put on a stunning display that was a Kreutz sungrazer. A more recent example of a comet belonging to this class was C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy). This group of comets was thought to have originated from a breakup of a massive comet in 371 BC that was observed by Aristotle, Ephorus, and others. This comet was so bright that it was able to cast shadows on the ground at night! The first comet to ever be photographed was Dontai’s Comet in the year 1858. A portrait photographer utilized a 7-second exposure and an f/2.8 lens to take a photograph of the comet in the sky, however this photograph has not survived history. Later, the Great Comet of 1881 was photographed and is among the first ever images of a comet in the sky. Most recently, Comet NEOWISE (C/2020 F3) put on a stunning display for northern hemisphere observers, becoming one of the brightest comets visible to the naked eye in over two decades. And then of course we have Comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) expected to put on a good display in the coming weeks – more information here!

Gear Recommendations

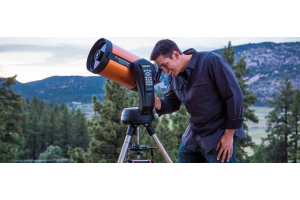

If this is your first time photographing a comet, we recommend sticking with a small, lightweight setup that you can use for purposes beyond astrophotography. Similar advice can be found in our No Fuss Telescope guide and in our Astrophotography on a Budget guide. We recommend sticking with relatively simple setups even for more advanced astrophotographers. The reason for this is simple - comets are often close to the Sun, and quickly swamped out by the rising Sun or lost in the evening glow of sunset. Having a complex setup that you have to polar align, balance, integrate with a ASIAIR or Mini-PC, etc. will quickly run into a wall of diminishing returns. If you’re fussing with gear like you would for an 8 hour+ astrophotography session, you may find by the time you’re ready to shoot the comet, the comet will be gone for the night. Obviously, not all comets run into this limitation, but many of the truly bright and photogenic ones pose this type of challenge.

The Askar SQA55 Refractor is an excellent choice for photographing larger comets like the quickly upcoming C/2023 A3 comet, especially when paired with an APS-C or larger sensor camera. With its 264mm focal length and wide f/4.8 aperture, it strikes a perfect balance between light-gathering power and portability. This telescope is ideal for capturing comets that move slowly across the sky, offering an image scale that reduces the appearance of motion blur as the comet slowly moves between exposures. A larger focal length telescope, in comparison, might struggle with a larger comet with a high apparent motion for this reason. Its five-element lens system ensures sharp, detailed images, while the compact, 4 lb. design makes it easy to take on the go, perfect for both astrophotography trips and spontaneous sessions. The Askar SQA55’s Petzval design also simplifies the setup process by eliminating the need for a separate field flattener, making it a hassle-free solution for beginners and advanced users alike.

For those who prefer not to use a telescope, a 135mm camera lens paired with a DSLR offers a versatile alternative. This focal length is ideal for capturing the full coma and tail of a comet while still providing enough zoom to resolve details. It also complements the comet’s slow drift across the sky, giving you a manageable exposure time that minimizes the need for complex tracking setups. With a larger sensor like APS-C or full-frame, a 135mm lens (or similar) allows for wide-field comet photography while maintaining a perfect balance between image scale and field of view, making it an excellent option for both beginners and seasoned photographers. Faster optics will also improve your image, although the pre-dawn/twilight light will prove challenging to manage light reaching your sensor depending on the comet’s angular separation from the Sun, and you may need to stop-down your optics in order to compensate for the background sky brightness.

As for mount solutions, the Sky-Watcher Star Adventurer 2i is an excellent, budget-friendly tracking mount for photographing comets. Its compact and lightweight design, weighing just 2.2 pounds, makes it highly portable and easy to bring along on comet-watching trips to remote locations to get a clearer view of any comets low on the horizon away from light pollution. Its stable tracking capabilities, especially for slower-moving comets, make it a great choice for photographers looking for simplicity and portability without breaking the bank. Whether you're capturing a time-lapse of a comet’s journey or photographing its detailed coma and tail, this mount provides the flexibility and ease of use needed to get the perfect shot. Slightly heavier, the Sky-Watcher GTi mount has GoTo capability, which would make it easier for you to find the comet if you know it’s right ascension/declination but cannot spot the comet naked eye. However, we’ll also note some comets are large and bright enough to where you don’t need a fancy tracking mount at all. A DSLR with a tripod and a ½” exposure might be all you need to capture views of the comet.

Exposure and Imaging Techniques

There are many ways to photograph a comet. The most important thing is that, unlike with dim deep-sky objects, you do not want to do 2+ minute exposures. This is because the comet is moving rapidly compared to the stars in the background sky. While it’s true you could auto-guide on the nucleus of the comet, you’ll find the stars in the background begin to streak even if the comet is perfectly round while adding extra difficulty to an already challenging image session. Keep your exposures within 60 seconds for the most optimal results. This will keep both the stars and the comet fairly round and sharp in your sub-exposures. If you’re doing something widefield, it might be nice to find a good foreground subject. A tree, windmill, mountain, or interesting rock formation framed up with the comet will add to the photograph and create a wider appeal to your image. If you want a sharper, less-noisy image with better color, we recommend taking multiple exposures and stacking the images. This will increase the signal-to-noise ratio of the comet. Take anywhere from 15-30 minutes of images on the comet if you can, as any longer will make post-processing more challenge due to the motion of the comet against the background stars. No matter what gear you use, focus is critical—make sure to perform a focus check on a bright star before starting your imaging session. A bahtinov mask or similar will aid in your focusing technique.

Post-Processing

DeepSkyStacker

Processing images of comets can be difficult, but software exists to make stacking comet images easier. One way to process your images of a comet is to use DeepSkyStacker’s comet alignment and stacking tool.

- Under “open picture files” drop your images of the comet, and then check them all (excluding any you don’t want to stack). You’ll see the date/time, image size, ISO, file-type on the right-hand side next to each file.

- Register each image as you would for a normal dark sky image, try to aim for about ~100 stars being registered.

- Now go to “Edit Comet Mode”, the green star/comet on the right hand side of the image. Under the first frame of the comet in your list, center your cursor over the nucleus (brightest part) of the comet and click once. A purple circle will appear over the nucleus that you have indicated.

- Under Options go to Settings > Stacking Settings > Comet > Stars + Comet Stacking, and press “okay”.

- Now go to “Stack checked pictures” > Click “Okay” to begin stacking.

- The result will be an image (.tiff/.fts) that you can then process in Photoshop or PixInsight to your liking!

Photographing a comet is a truly unique and rare experience that astrophotographers rarely get to experience in its full glory. With advancements in gear, including compact telescopes and even smartphone cameras, comet photography has become more accessible than ever, making it possible for amateur astronomers to take breathtaking images without breaking the bank.

Whether you're a seasoned astrophotographer or just getting started, the tools and techniques mentioned in this guide can help you achieve striking results. By understanding the importance of gear, exposure times, and post-processing, you’ll be well-prepared to capture the next great comet, including the upcoming C/2023 A3.

Learn More

For more personalized advice or to explore the latest equipment, visit the High Point Scientific AstronomyHub, where you'll find a wealth of resources and a community ready to help you on your astrophotography journey.