In our world of point-and-shoot photography, it’s easy to take for granted how far we’ve come. We don’t always think about how difficult it was to capture those first few images of, well, anything, and how significant the emergent field of astrophotography has been for scientific research. What is now a popular hobby was once just an idea, and it’s all thanks to the pioneers of the field that we can appreciate stunning images of the stars, planets, and galaxies today, all with our very own equipment. Here’s a brief look into the past and the history of the hobby that we love so much.

Gazing at the Stars

It’s impossible to talk about astrophotography without first mentioning the invention of telescopes. After all, even today the pictures we capture and techniques we use require the use of telescopes, and without them, the deep-sky images that inspire generations of astrophotographers would be lost to us.

The first telescopes we have records of were invented in 1608 by at least two, and possibly three, separate eyeglass-makers in the Netherlands. Shortly after word got around about the invention, Galileo Galilei came up with his own design, and the true potential of telescopes was discovered. He pointed his telescope at Saturn and saw its rings, Jupiter and its moons, the craters on our own moon, and even the sun (which is of course highly ill-advised, but he did see some amazing things, such as sun spots).

One could almost argue that this is where astrophotography started, but in a different form. Galileo sketched what he could see through his telescope, including the details on the surface of the moon and the ever-changing positions of Jupiter’s moons. Of course, you can only get so far with sketches, but it would be several hundred years before a more efficient and accurate form of image-capturing would even be invented, let alone used for space observation.

Image Credit: Scala/Art Resource, New York

The Rise of Photography

Early photography (and even as recently as during the age of the film camera) was a marriage between optics and chemistry. It relied on an understanding of how to capture light and then “keep” it using chemicals that react to light in specific and predictable ways.

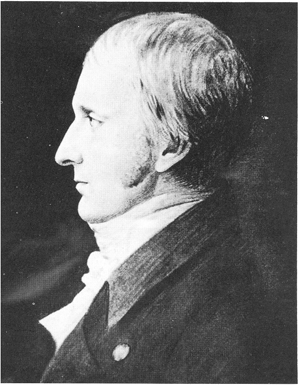

Thomas Wedgwood was the first person we know of who thought to use this technique of image capture using chemicals, and while his early experiments were largely successful, there were still problems with the process. While he could indeed capture negatives using a camera obscura (Latin for “dark room”) and paper coated with silver nitrate, once the paper was exposed to light, the rest of the paper turned dark and the image was lost. Knowledge of his experiments made its way from his home in England over to France, where they inspired the next round of attempts to discover a better method.

Nicéphore Nièpce would become the Frenchman to fix his name in the history books when he came up with a method to not only capture images but keep them permanently. His method was known as heliograph photography, and it used a pewter plate coated in bitumen combined with light from the sun (and an exposure time of several days). Just like that, in 1822, the world had its first photograph. The view from Nièpce’s window is the earliest surviving photograph we have, and it represents a major leap in technology. About 10 years later, Louis Daguerre, Nièpce’s partner in the development of photography, made a breakthrough. By adding iodine vapor to silver-coated copper plates and then later exposing it to mercury fumes, he could tease out a better image in less time.

Finally, we had the two things we needed to get astrophotography off the ground and into the sky.

Photo of Thomas Wedgwood

Combining the Two

John Herschel dabbled in a little bit of everything. His father, Willam Herschel, was an exceptional astronomer, and that talent passed on to his son who was also skilled in mathematics, chemistry, and significantly for us, photography. When he learned about the technique developed by Daguerre (known as daguerreotype), he immediately set out to improve it. He’s even credited with coining the term “photograph,” which comes from the Greek terms for “light” and “writing.”

Photography needed to be developed further in order to be useful in astronomy, and Herschel among many others pursued these developments with fervor. In 1840, the moon became the first astronomical object to be photographed. Astronomers set their aspirations even higher, with the goal of being able to use long exposure times to reveal celestial objects the human eye can’t see. This goal not only required better photography methods but also better telescopes that could capture more light. The two technologies grew together, with improvements to one necessitating improvements to the other. As more and more observatories began popping up and more astronomers turned their attention to astrophotography, many firsts in the world of astronomy and astrophotography took place.

Two years after the moon was immortalized, in 1842, the first image of a partial solar eclipse was captured by G.A. Majocchi, an Austrian astronomer, using the daguerreotype method. Another two years would pass before the first photographs of the Sun would be revealed, one of which still survives to this day. They were captured by two astronomers at the observatory in Paris, Armand Hippolyte Louis Fizeau and Jean Bernard Léon Foucault.

The next astrophotography first occurred in 1850, when the first photo of a star was taken by John Adams Whipple and William Cranch Bond. The star was Vega, and it was captured once again by daguerreotype.

Daguerreotype was clearly the method of choice for many years, but there was plenty of room for improvement. In 1851, one such improvement was made. A photographer named Frederick Scott Archer wanted to increase the resolution of photos, so he spread nitrated cotton dissolved in ether and alcohol (called collodion) along with other chemicals on glass. This new method, known as wet plate collodion, was much cheaper than daguerreotype and quickly took over the photography world. Wet plate collodion photography was responsible for revealing the photosphere of the Sun in an 1854 photo, and later it also revealed the double star Mizar.

Image Credit: Earliest known surviving photograph of the Moon, a daguerreotype taken in 1851 by John Adams Whipple

A series of successes and failures followed for the next twenty or so years, with more photos of the Sun and moon emerging, as well as methods for capturing a celestial object’s spectrum. Then, in 1874, a new invention emerged called the photographic revolver, and it allowed a series of images to be taken that captured movement (a technique known as chronophotography). Using the photographic revolver he invented, Pierre Jules César Janssen captured Venus as it moved across the face of the Sun.

Favorite targets for many astrophotographers are nebulae, but it wasn’t until 1880 that astronomers were finally able to capture a nebula on film. Orion was the first nebula to be photographed, and its photographer was someone who is very well known these days as a pioneer in the field of astrophotography. The man was Henry Draper, and in addition to photographing a nebula for the first time, he also took several photos of the moon and captured the spectra of nearly every bright star in the sky, and he did this all with equipment he made himself.

He also took one of the first successful photos of a comet in 1881, though he doesn’t hold the title of the very first. That belongs to Jules Janssen, and the results were spectacular.

Up until this point, no successful, detailed images of planets had been captured. These elusive targets would remain out of reach until 1885 and 1886 when Jupiter and Saturn finally revealed themselves to photographers. Mars followed shortly after, and while astrophotography remained important to astronomers, most turned their attention to spectra photos in order to learn more about the cosmos. The most famous example comes to us from Edwin Hubble, who used images of Cepheid variables and the redshift of galaxies to not only estimate the distance from our galaxy to Andromeda but also put forth the paradigm-shifting idea that galaxies are moving away from us and therefore the universe is expanding.

Even considering how far we’ve come, to the point where astrophotography can tell us about the state of the universe as a whole, there’s plenty of room for improvement. Still, it was due to those early pioneers that we reached the point where those of us without scientific training have the technology and know-how to capture nebulae, distant galaxies, our neighboring planets, and other bits and pieces of this amazing universe.

Astrophotography Timeline

- 1822 - Nicéphore Nièpce - View from Window - World’s first photograph is captured

- 1840 - John Draper - Moon - The moon becomes the first celestial object to be photographed

- 1842 - G.A. Majocchi - Solar Eclipse - First partial phase solar eclipse captured

- 1850 - John Adams Whipple and William Cranch Bond - Vega - Vega becomes the first star to be photographed

- 1854 - Joseph Bancroft Reade - Sun - Better photographs of the Sun reveal the photosphere

- 1874 - Pierre Jules César Janssen - Venus Transit Across Sun - Photographic revolver is invented to capture Venus moving across the Sun

- 1880 - Henry Draper - Orion Nebula - A nebula is photographed for the first time

- 1881 - Jules Janssen - Comet - First photos of a comet taken by Janssen and others

- 1885/86 - The Henry Brothers - Jupiter and Saturn - Planetary bodies are photographed for the first time successfully

- 1924 - Edwin Hubble - Cepheid Variables - Hubble uses Cepheid variables to estimate the distance to Andromeda

- 1929 - Edwin Hubble - Galactic Redshift - Hubble identifies redshift degree of galaxies indicating universal expansion

Learn More

Interested in learning more about astrophotography? Not sure where to begin? Check out our Astronomy Hub to learn more!