Look through any telescope at the Moon and you’ll immediately notice something you can’t see with just your eyes - craters. They’ve scarred the Moon’s face and cast shadows over its surface for millions of years - and yet no one knew of their existence until the early 17th century. But how did the craters form? Is the Moon the only world to have them? And what are some good craters to look at on the Moon?

A Perfect Universe - Without Craters

Before the invention of the telescope, it was widely believed that the Moon was a perfectly smooth sphere, as it was created by God and God was without imperfection. However, when astronomers turned the first telescopes toward the Moon in the early 17th century, they saw the craters for the first time. They also noticed that the craters cast shadows, which simply wouldn’t be possible if the Moon was as smooth as people believed.

The Moon then was clearly not a perfectly smooth sphere, otherwise, there would be no shadows. But how did the craters get there?

Volcanoes… or Something Else?

At first, it seemed natural to believe these craters were the dormant caldera of volcanoes. After all, these were known to exist on Earth, and it made sense they might also be on the Moon.

In 1665, the English astronomer Robert Hooke first suggested they might also be formed by meteoroids. Known as the impact theory, proponents believed the craters were the result of rocky objects, such as asteroids, striking the Moon’s surface.

The two ideas co-existed for roughly three hundred years, with the volcanism theory bolstered by numerous reports of active volcanism on the Moon. For example, William Herschel, discoverer of the planet Uranus, was the first to make such a report in the spring of 1783, and although his observations were later refuted, astronomers continued to report similar phenomenon over the years.

The impact theory, while far less popular, wasn’t without its supporters either, but it wasn’t until 1960 that the tide began to turn in its favor.

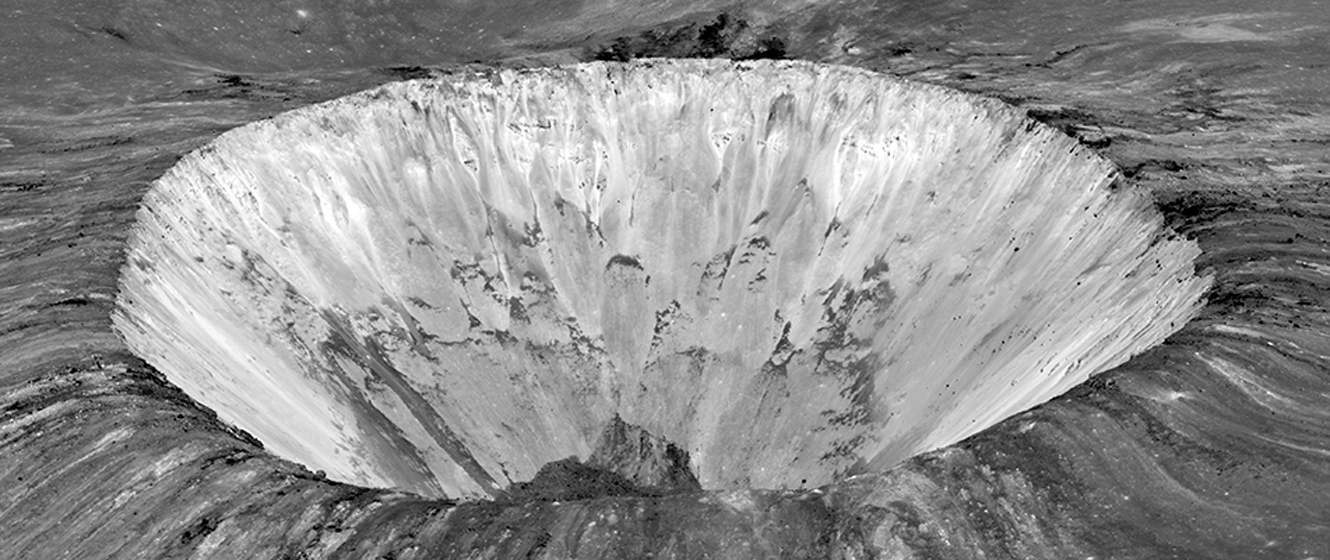

In 1891, a geologist named Daniel Barringer discovered the large crater in Arizona that would later bear his name. He believed it was formed by an impactor, but the majority of his colleagues believed it had been formed by a sudden venting of volcanic steam.

Barringer, however, was not to be swayed, and his beliefs were affirmed when geologist Eugene Shoemaker studied the crater for his Ph.D. in 1960. He found a compelling similarity between the crater and craters formed at nuclear test sites, but it was the discovery of shocked quartz at Barringer Crater that truly closed the deal.

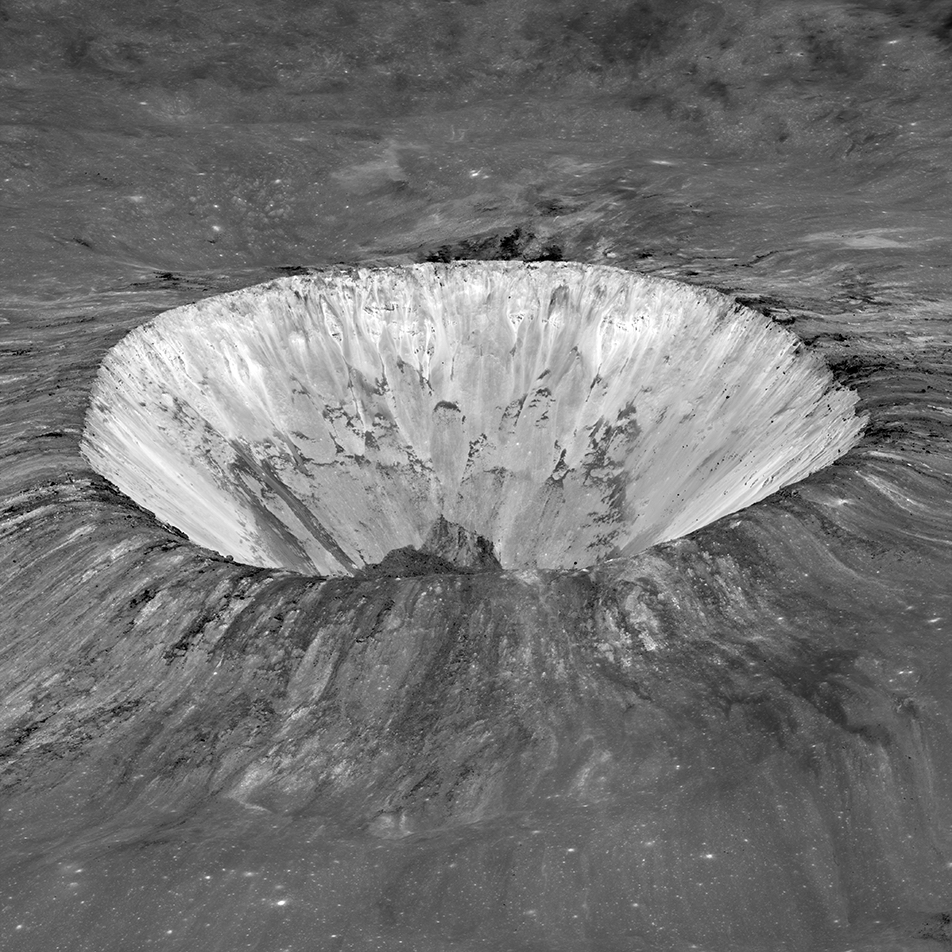

Image Credit: NASA

Shocked quartz is formed under the same intense pressure that would result from a projectile impacting the ground at high speed, which left Shoemaker in no doubt as to the origin of the crater. As far as Shoemaker was concerned, the only way this crater could have formed was if a meteorite had struck the ground.

Barringer’s crater (now commonly known as Meteor Crater) became the first crater on Earth known to be formed in this way. Suddenly, geologists and astronomers alike were rethinking their beliefs about the craters on the Moon, but the scientific community remained divided.

Ex Luna Scientia - From the Moon, Knowledge

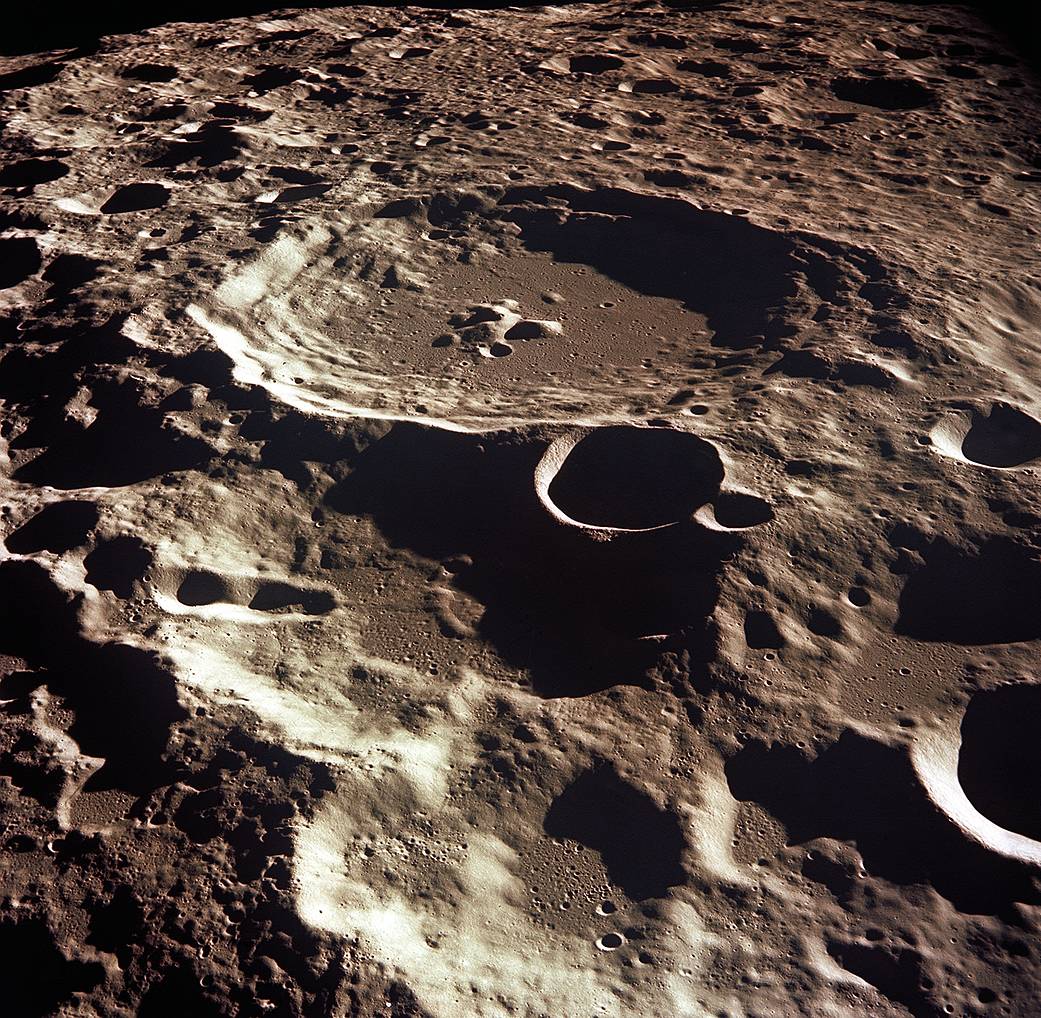

The late 1960s and early 1970s saw humanity take its first steps on the Moon’s surface. While the goal of Apollo 11 was primarily to land the first man on the Moon, later missions would have a focus on science, including geology.

Shoemaker himself had a hand in training the astronauts, and as a result, those astronauts returned hundreds of pounds of invaluable rock to Earth. Since the Moon has no atmosphere or weather, these rocks had remained untouched and in the same pristine condition for millions or even billions of years.

Some of these rocks had compositions matching carbonaceous chondrite meteorites. These meteorites are known to have their origins in the asteroid belt, indicating the rocks are remnants of the meteorite that formed the crater.

There are also countless examples of craters overlapping. This happens when a meteorite impacts an existing crater and partially destroys it, forming a new crater in the process.

It’s now an accepted fact that the vast majority of craters on the Moon were formed by meteorite impacts. However, that’s not to say there are no volcanoes on the Moon. Our nearest neighbor was volcanically active for billions of years, but the majority of this activity ceased about a billion years ago and the Moon has been relatively quiet ever since.

With no active volcanoes on the lunar surface today, the Moon is essentially a cold, inert world.

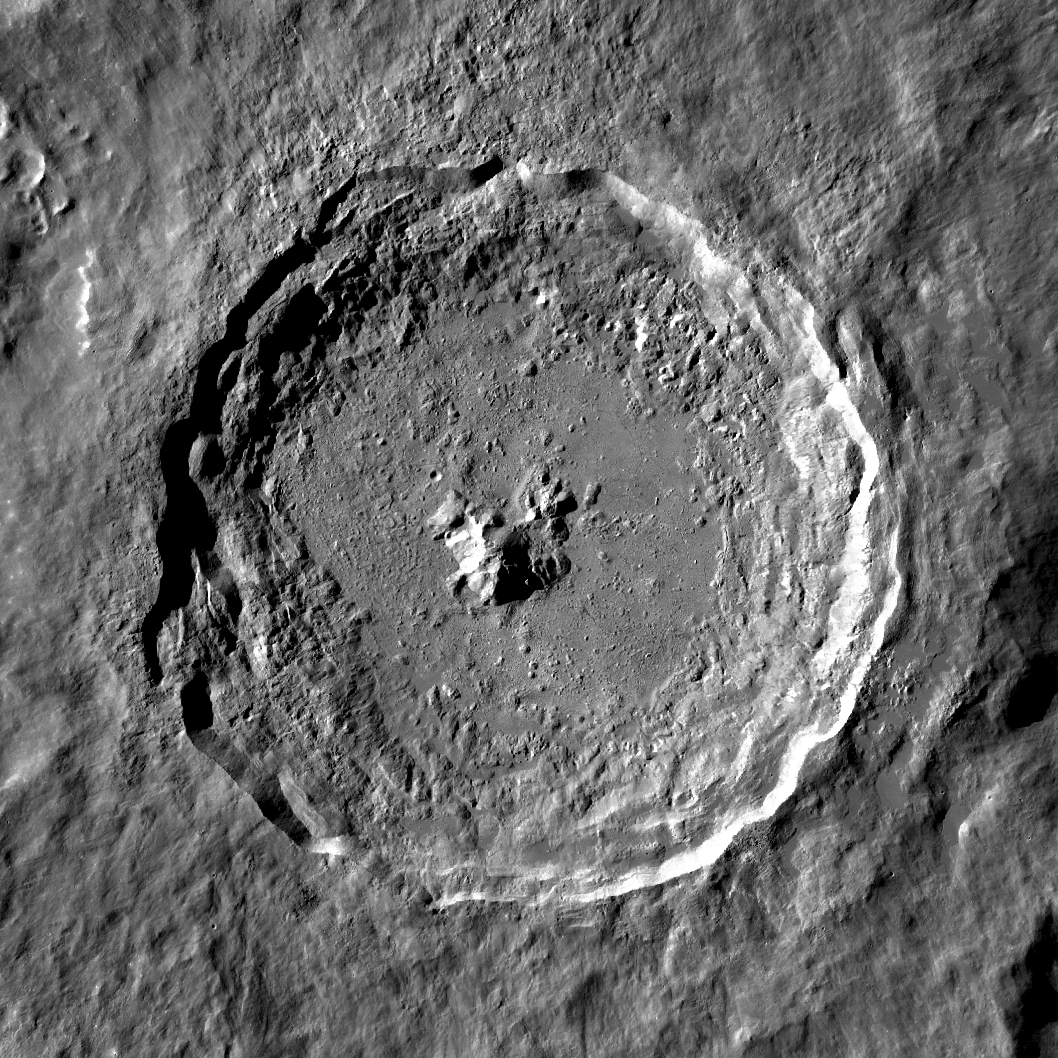

Image Credit: NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

Are There Craters Elsewhere in the Solar System?

In July 1965, before the Apollo astronauts set foot upon the Moon, the Mariner 4 space probe took the first pictures of the surface of another planet - Mars. Although the technology was primitive in comparison to the cameras in use today, scientists were able to see craters littered across the Martian landscape.

The scene was repeated nearly nine years later when Mariner 10 became the first space probe to fly past Mercury. Like the Moon, the smallest planet is covered in craters, but it doesn’t stop there. Almost every rocky object in the solar system, including the Earth, has craters. Even asteroids, the cause of many of the craters themselves, have craters, formed by collisions with smaller objects.

Do Craters Have Names?

With all these craters scattered across the solar system, it makes sense that there should be a way to identify them. Otherwise, it would be difficult for astronomers to know which craters were being studied or discussed, both by themselves and by others.

Craters on the Moon are typically named for deceased scientists and explorers, a tradition that started in the mid-17th century. For example, the craters Tycho and Copernicus were named for Tycho Brahe and Nicolaus Copernicus, respectively. On the far side of the Moon (which is much more heavily cratered), you’ll find Gagarin, named for the first man in space, and in Mare Tranquillitatis, close to Apollo 11’s landing site, you’ll find the crater Armstrong.

Craters on Mars are named a little differently. If they’re larger than 37 miles (60 kilometers) wide, they’re named for scientists and science fiction writers, but there are a few noteworthy curiosities. For example, H.G. Wells, author of The War of the Worlds, has his crater on the Moon, while Orson Welles, the film director whose infamous radio dramatization of The War of the Worlds caused panic in 1938, has his crater near the equator on Mars.

Unusually, craters smaller than 37 miles are named for towns on Earth. For example, the crater Albany is named for Albany, New York, while Aspen is named for Aspen, Colorado.

Craters on Mercury are named for deceased writers, artists, and composers, such as Mark Twain, Michelangelo, and Beethoven.

The planet Venus has fewer craters, as its dense atmosphere causes many of the meteorites to burn up before they hit the ground. However, since the planet is the only one named for a female deity, its craters are either named after famous women or have been given female names.

For example, you’ll find the crater Austen, named for the British author Jane Austen, as well as first names from all around the world, such as Bette from Germany, Mariko from Japan, and Teura from Polynesia.

Image Credit: NASA / Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter

What Are Some of the Best Craters on the Moon?

Although you’ll need a telescope to see the craters themselves, you can see the location of several craters with binoculars, or even just your eyes. Perhaps the most obvious is the crater Tycho, located in the Moon’s southern hemisphere.

It’s best observed around the full Moon, and you can easily see its location with your naked eye. At full Moon, sunlight directly strikes the crater and illuminates the bright rays that stretch more than 900 miles (15,000 kilometers) across the lunar surface. These rays are the result of debris being ejected when the impactor first collided with the Moon and formed the crater.

It’s a similar story with Copernicus, in Oceanus Procellarum. It also has a ray system and although those rays make the crater easy to locate with binoculars, they’re not nearly as impressive as Tycho’s.

However, this 58-mile (93 kilometer) wide crater is spectacular through a telescope, but be sure to catch it when the Moon is about 8 or 9 days old. That’s when the crater lies on the terminator - the dividing line between the lunar day and lunar night - and the Sun casts spectacular shadows across the crater’s walls and floor.

Lastly, look out for the crater chain of Theophilus, Cyrillus, and Catharina on the northwestern edge of Mare Nectaris. You’ll need a telescope to see them and they’re best seen when the Moon is about four or five days old. Like Copernicus, this famous crater trio is a breathtaking sight when all three are on the lunar terminator.

Image Credit: NASA / Lunar and Planetary Institute

While you’re looking, keep your eyes open - although the vast majority of craters were formed millions of years ago, there are still plenty of small, rocky meteoroids floating through space. In 2019, one such rock was seen striking the Moon during a total lunar eclipse, causing a momentary flash that lasted a mere quarter of a second. Blink, and you would have missed it!

Learn More

Interested in learning more about the Moon? Not sure where to begin? Check out our Astronomy Hub to learn more!

This Article was Last Updated on 08/18/2023