Of all the planets in the solar system, none have captivated the public’s imagination more than Mars. This small world, only about half the size of the Earth, has long been the subject of speculation regarding alien life -- with observers, writers, and moviemakers all portraying the planet as the habitat of beings with an envious eye on Earth. But what can you see with your own eyes?

A Coppery, Rather Than Red, Planet

Mars, along with the planets Mercury, Venus, Jupiter, and Saturn, has been known and observed for thousands of years - long before the invention of the telescope. Fourth in distance from the Sun (after the Earth), it’s visible on most nights throughout the year in either the evening or morning sky.

With a year that lasts 686 days, it takes nearly twice as long as the Earth to orbit the Sun and is only at its best roughly once every two years. At that time, it appears as a brilliant, pale orange or coppery “star” that almost outshines everything else.

The Sun and Moon are both obviously brighter, but in terms of the planets, Venus is the only one that consistently beats Mars in brightness. Jupiter can sometimes equal or outshine the red planet, but Mercury, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune are all fainter. And while there are plenty of stars that are brighter than the planet when it’s at its faintest, none come close when Mars is at its best.

Just like the other planets, you can only see Mars as a brilliant point of light with just your eyes, and you’ll need some form of optical aid to see anything of the planet itself. Unfortunately, binoculars really aren’t powerful enough to improve the view, and the planet will only ever appear as a bright, starlike point of light - even when it’s closest to Earth.

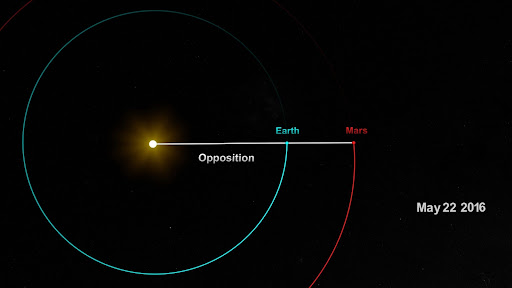

Even with a telescope, the planet is only really best observed when it’s opposite the Sun in the sky (called opposition) and therefore visible throughout the night. At this time, Mars is closest to the Earth, so it’s at its brightest and appears largest through a telescope. Unlike the planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, this only happens roughly once every two years.

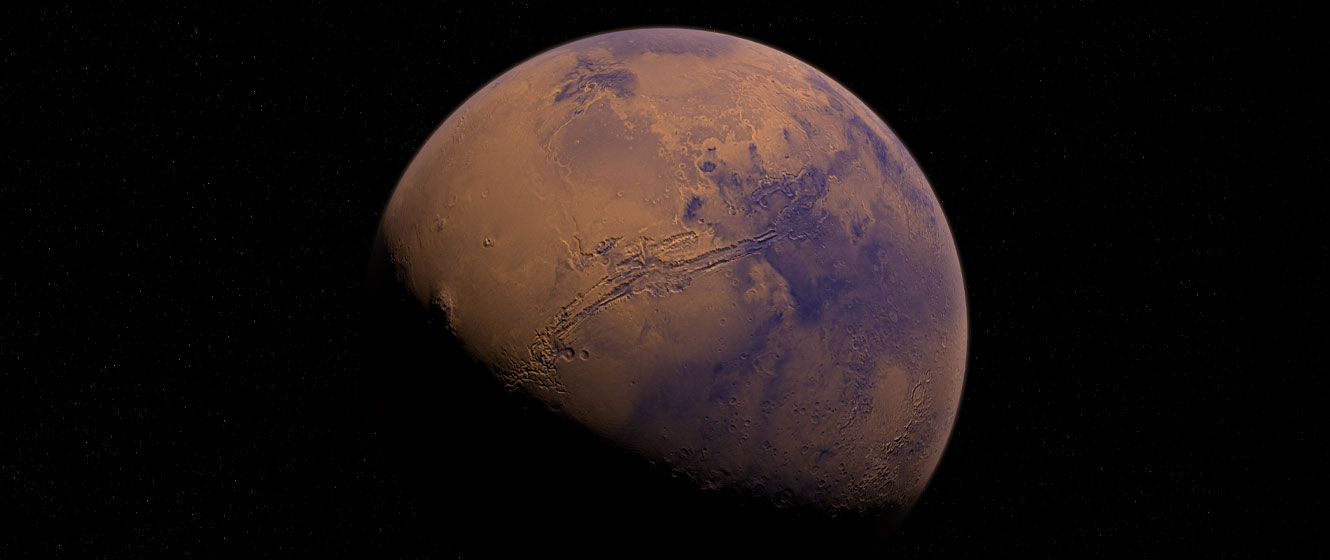

Image Credit: NASA/JPL

Dark Marks and Imaginary Canals

That being said, even a small telescope can prise out some details. When the planet is close to opposition it will show a brilliant, pale disc even at a low magnification of about 35x.

Increasing the magnification also increases the size of the disc, with less contrast between the planet and the background sky. As a result, you should start to see some faint, gray surface markings at around 60x or 70x.

Once you reach a magnification of about 100x, the planet will take on a pinkish color, with the surface features becoming more easily seen. In particular, look out for a reasonably well-defined, triangular feature known as Syrtis Major. Around the same area is Mare Tyrrhenum, a dark strip that appears to cross the mid-southern hemisphere of the planet.

If you have a larger telescope (and arguably, an active imagination) you might also see some thin, faint grey lines connecting the darker patches. That’s what the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli observed during the opposition of 1877. He described them as channels, or grooves, on the surface, but the Italian word canali was misinterpreted into English as canals.

As a result, many believed the lines were waterways built by a thirsty martian race in a desperate effort to save their dry, dying planet. The reality, of course, is that no such Martians exist, but the idea may well have sparked a number of fantastic science fiction stories!

While the lines might elude many of us, we can still watch the other markings come and go as the planet turns. A day on Mars is just slightly longer than a day on Earth, with the planet taking 24 hours and 39 minutes to complete one turn on its axis. As a result, you can start your evening with Mars and, if you’re outside for a few hours, come back to it near the end of your observing session and see how far the markings have moved.

Alternatively, observe the planet at a specific time one night and then return at the same time over the next few nights. As the planet’s day is 39 minutes longer, you’ll see the markings appear to gradually shift as the planet’s rotation falls out of sync with our own. Check out Sky & Telescope’s Mars Profiler to see which features should be visible when you observe.

If you’re looking to enhance the surface markings, try either a yellow or orange filter. These not only subdue the light from the brighter area of the disc but can also help to steady the image through your eyepiece.

Image Credit: NASA's Scientific Visualization Studio

Shape Shifters & Two Tiny Moons

Depending upon which hemisphere is tilted toward the Earth, you could also catch a glimpse of one of the polar ice caps. Of the two, the northern cap is more stable, while the southern cap can shrink and grow quite significantly. If opposition coincides with winter in the martian southern hemisphere, then the cap should be quite easily seen.

Through a small telescope, you can spot the ice caps at magnifications below 100x. Only one is typically easily seen at any given time, but it will appear as a starlike point on the very edge of the planet.

The planet itself might also appear to change shape over time. This isn’t as crazy as it sounds! When Mars is in opposition, we’re looking directly at the disc of the planet, fully illuminated by the light of the Sun. In that respect, it appears fully circular, like the full Moon from Earth.

But take a look at the planet roughly four months before or after opposition - when the orbital angle between the Earth and Mars is widest - and you’ll see Mars in a gibbous phase, like the Moon when it’s between the full and half moon phases.

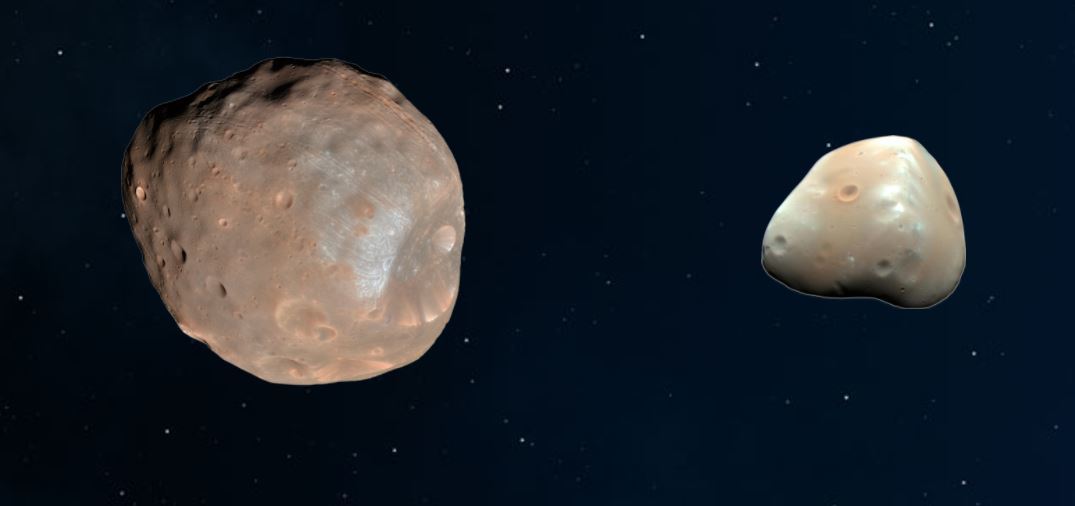

There’s one last challenge that owners of large telescopes can attempt; spotting the two, tiny moons of Mars. Named Phobos and Deimos, these tiny asteroid-like objects are very faint and difficult to see.

Your best bet will be when the planet is in opposition, and even then you’ll need to wait until the moons are farthest from the planet. Unlike our own Moon, which takes almost a month to orbit the Earth, Phobos takes less than 8 hours to complete an orbit of Mars while Deimos spins around the planet in a little more than 30 hours.

Checking a magazine, such as Astronomy, Sky & Telescope, or Sky at Night, or using astronomical software or a smartphone app can help you to identify the best times to make your observations.

Image Source: NASA / Mars Exploration

You’ll also need to make sure that Mars is just outside the field of view, as the brightness of its disc can easily overwhelm the faint light coming from its two satellite companions. Good luck!

Imaginary Martians and canals aside, Mars can be a challenging but rewarding target for patient observers. It doesn’t reveal its secrets easily, but careful planning can pay dividends if you’re prepared to invest the time. Don’t let another opposition pass you by without pointing your telescope in its direction and discovering all that the red planet has to offer.

Learn More

Interested in learning more about the planets in our solar system? Check out our Astronomy Hub!

This Article was Last Updated on 07/27/2023